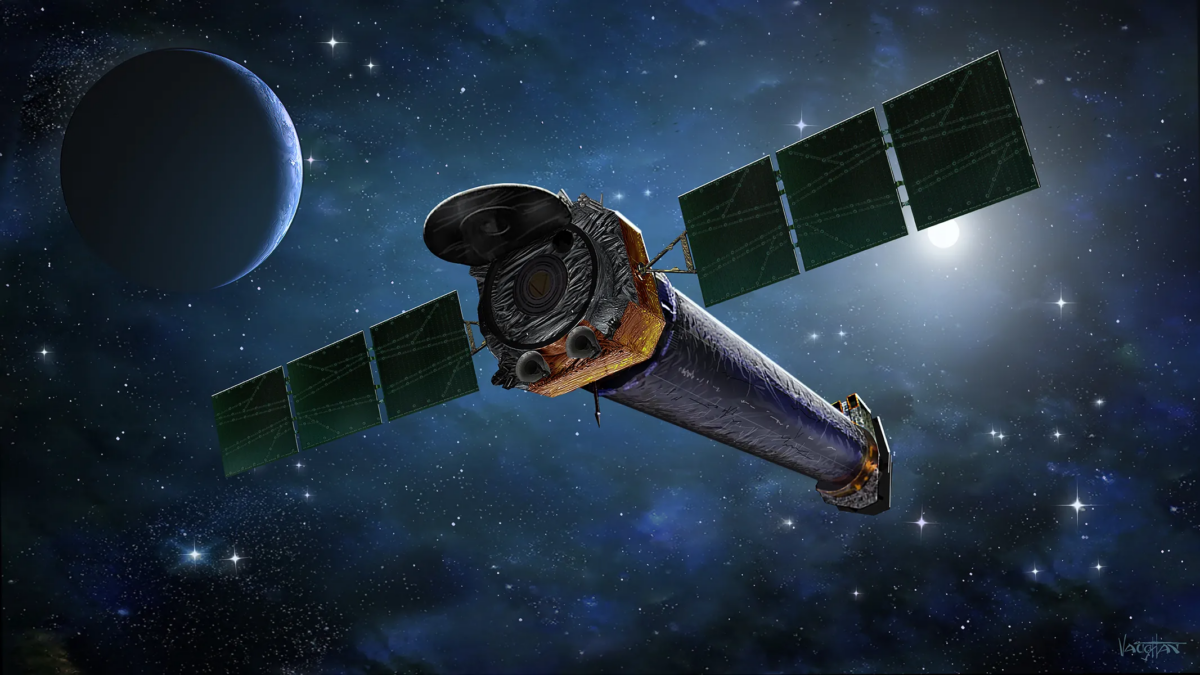

Artist's impression of the Chandra X-ray Observatory. Credit: NASA/CXC and J. Vaughan

All space missions come to an end. Some die quietly of old age, running out of fuel or power. Some go out in a blaze of glory, plunging into an atmosphere and burning up, sending back data at the last. Others self-destruct, never reaching their intended targets—exploding on the launch pad or ending up as an accidental impact crater on an alien world.

But earlier this year, when NASA announced that the Chandra X-ray telescope was nearing the end of its days, it wasn't for any of those reasons. The telescope was fully operational and still producing cutting-edge science. Rather, NASA was facing a budget shortfall and deemed the observatory expendable.

In NASA history, perhaps no mission this large, productive and fully operational has been cancelled simply because the agency decided not to pay the costs.

Chandra has the highest resolving power of any X-ray telescope ever built, and for 25 years has provided astronomers with penetrating views of the invisible universe, including star explosions, evidence of black holes, and other exotic objects. Today it remains one of the most productive and in-demand observatories in NASA's portfolio. In 2022, NASA reviewers rated Chandra as one of its most successful ongoing programs, on par with Hubble.

But in March, officials put it in their crosshairs, scheduling 80 layoffs representing most of its operational team starting in September. That same month, NASA requested just $41 million for Chandra in the agency’s 2025 budget — a 40 percent reduction — in order to begin an “orderly drawdown of the mission to minimal operations.”

The move has sparked a notable outcry in the global astronomical community, and it has had its impact. At least a recent interview by NASA Administrator Bill Nelson offers hope that the telescope can be saved. For now, Chandra remains in limbo, but NASA is expected to make an announcement next month about the mission's near-term fate.

For many researchers, it doesn't make sense to cut costs in order to pursue a productive mission like Chandra. Chandra's annual operating budget is $68 million, just 1.8 percent of the total NASA has spent on the telescope since 1999. One scientist compared ending the mission to having a beautiful, perfectly maintained house with a paid mortgage and burning it down to avoid a year of utility bills.

Chandra also maintains America's lead in X-ray astronomy, a field that American researchers founded in the early 1960s. Scientists say the sudden closure of Chandra would leave a discovery gap for decades and that its European and Chinese counterparts are no match for Chandra's sensitivity and resolution.

A technological marvel

When Chandra blasted off into space on July 23, 1999, aboard the space shuttle ColumbiaIt was a revolutionary advance over the previous generation of X-ray telescopes.

“Chandra is a technological marvel,” says David Pooley, an astronomer at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas, citing the exceptional smoothness of its four concentric pairs of mirrors. Unlike traditional telescopes, they are oriented at extremely low angles to capture X-rays that would otherwise pass through glass. “No other X-ray telescope has ever had spatial resolution approaching that of Chandra,” Pooley says. “It’s very difficult to make mirrors that focus X-rays that precisely.”

Just three years after its launch, the observatory proved its worth by helping Riccardo Giacconi win the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physics for his Chandra-based research into the ubiquity of black holes in the universe. Since then, it has captured the shock waves from supernovae, the cooling rate of a neutron star, and pulses of radiation from black hole accretion disks.

But what makes the telescope's decommissioning vexing to researchers is not the telescope's legacy, but the loss of potential for continued operations. With 10 years of fuel on board and no serious mechanical problems, Chandra could survive until the next solar maximum a decade from now, scientists say.

Within weeks of NASA’s announcement in March, a movement called #SaveChandra was launched, energizing scientists and the public around the world with viral videos, petitions and letters to Washington.

The pushback has had some effect. In July, the Senate and House Appropriations Committees approved supportive budget proposals, with the Senate committing $72 million to Chandra’s “transformational discoveries,” while citing its vital synergy with the James Webb Space Telescope. On July 25, a House authorization bill was introduced that specifically directed NASA “to take no action to curtail or otherwise impede the continuation” of Chandra before the agency’s triennial review late next year. Although the actual federal budget for 2025 is still pending, congressional pressure may already be having an impact on NASA’s planning.

On August 13, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson told Ars Technica that the agency would strive to secure a new budget beyond its original request of $41 million and that layoffs would be limited.

“All science will be protected,” Nelson said. To some, this sounded like a victory. But scientists like Pooley, who helped draft a letter to NASA signed by more than 700 astrophysicists from around the world, remain concerned.

“The minimum budget should really be $72 million,” Pooley says. Astronomy“That’s what it takes to preserve science and fund the scientists who analyze the data.”

If Chandra is to be saved, there isn't much more budget to cut. A committee convened by NASA earlier this year found that the Chandra Operations Control Center outside Boston (where dozens of specialists work around the clock in a mission control room) was already running at bare minimum. Since launch in 1999, the mission's workforce has shrunk by 40 percent as specialists have become increasingly efficient at mission planning and operations.

We continue to lead the group

The current budget shortfall is not the first threat to Chandra's existence. Originally scheduled for launch in mid-1987, Chandra was sidelined in 1986. Challenger The disaster and the resulting budget constraints to rebuild the Space Shuttle Program. In 1992, a deepening national financial crisis nearly cancelled the project, then called AXAF, altogether.

Designed to carry six pairs of mirrors, the telescope proved too expensive and heavy for its own good, so NASA officials opted to scale back the design (and capabilities) to two pairs of mirrors and launch it on a Titan rocket. Frantic scientists negotiated a larger, more robust four-pair mirror design that could fit aboard a revived space shuttle.

The big compromise was that Chandra would be relegated to high Earth orbit, more than 130,000 kilometers away, far beyond a normal orbit of a few hundred kilometers. This meant that there would be no costly repairs by space shuttle crews. Given that crews had recently saved the Hubble Space Telescope with in-flight repairs, it was a huge gamble, but at least Chandra would finally make it into space.

In July 1999, astronomers watched with apprehension as the school bus-sized observatory was launched aboard the space shuttle. Columbia.

In retrospect, Chandra's distant trajectory proved providential. The 64-hour orbit places the observatory high above Earth's radiation belts for 55 hours at a time, facilitating unhurried, multi-hour observations that have revealed spectacular structures and revolutionized our understanding of cosmic life and death.

Chandra’s pioneering successes have made it clear to the rest of the world that X-ray astronomy pays huge dividends. The European Space Agency has committed more than €1 billion to its next X-ray flagship, Athena, and China is chasing it with a series of satellites and the recent launch of SVOM, which doubles NASA’s 20-year-old Swift mission focused on short-duration gamma-ray bursts.

“None of them have the combination of high spatial resolution and high spectral resolution that Chandra has,” Pooley says. “That’s why it’s such a bad decision to kill Chandra. There’s been nothing that could match it for 25 years, and there won’t be anything that can match it for decades.”