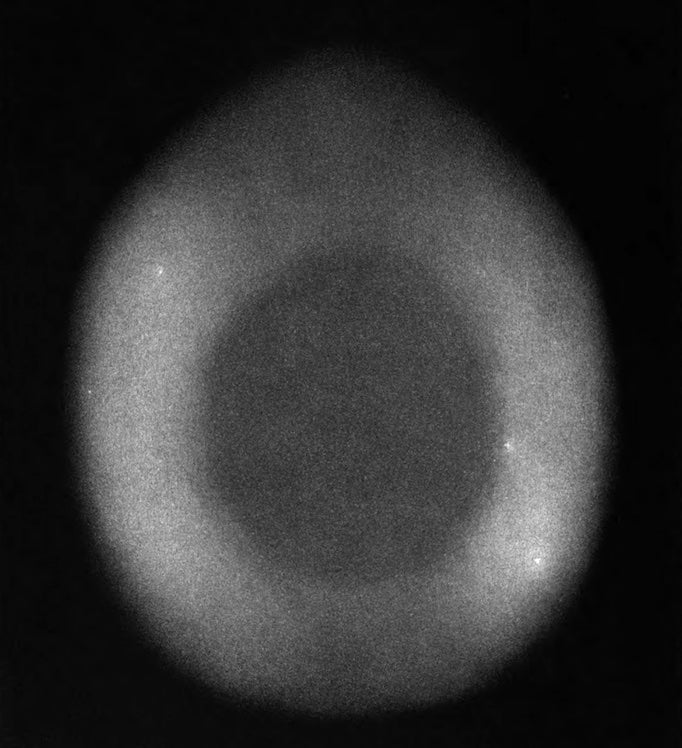

This 1874 lithograph was created by Étienne Léopold Trouvelot using the 15-inch refractor at the Harvard College Observatory, in order to measure the extent of the nebula. A glass plate with dark black lines was placed at the focus of the telescope to mark the location. Not surprisingly, it shows no central star. Credit: Annals of the Harvard College Astronomical Observatory (Vol. 8)/NASA ADS

The Ring Nebula (M57) in Lyra is one of the most beloved planetary nebulae in the night sky. However, its bright ring, which is the focus of most observers, can distract attention from what lies within.

This includes its central star, which is at the edge of vision and challenging to locate. So let’s dive into this nebulous doughnut hole, the twilight zone of deep-sky observing. As Rod Serling said, inside the Ring lies “a wondrous land whose limits are those of the imagination.”

Your next stop: the Ring Nebula

As with many discoveries, the Ring’s subtle features were detected in stages over time. When Charles Messier discovered the object on January 31, 1779, he observed it as a “little spot of light.” A few days later, his contemporary Antoine Darquier detected hints of a ring: its center, he said, appeared “a little less pale than the rest of its surface.” In 1785, William Herschel distinguished that region as a “dark, regular, concentric spot in the middle.” But it was not until decades later that Herschel’s son, John, noticed that the empty space was filled “with a faint but very distinct nebulous light… like gauze stretched over a hoop.”

When Messier discovered the object, it was thought that all nebulae might be unresolved star clusters. Initial attention was therefore focused on the Ring's ring to see if it could be resolved into stars, not the core.

But then a most mysterious discovery came about in that dark, twilight zone. Around 1795, the German astronomer Friedrich von Hahn began observing the Ring. Five years later, he announced that he had discovered a central star. Curiously, some observers using large apertures failed to see it, while those using smaller telescopes did. Even more astonishing is that Hahn made his visual discovery using a 12-inch Herschelian reflector with a speculum metal mirror that was probably only about 65 percent reflective (compared to today's silver coatings, which are about 98 percent).

To add to the mystery, during the five-year interval between the beginning of his observations of the Ring and their publication, Hahn himself lost sight of the central star, although he gives us a clue as to why: “A few years ago the interior of the Ring was so clear that I could distinguish a telescopic star at its center with my (12-inch) reflector. Now this telescope shows only faint clouds and the small star is no longer visible.”

It's a shame that, as far as I know, Hahn hasn't documented any magnification for these observations. If he had, perhaps it would have answered his own question. In short, if you can see the faint light inside the ring, your chances of seeing the central star are low. And this correlation is directly related to magnification. High magnification reduces the contrast between the ring hole and the background sky, making the central star more accessible. You'll need a magnification of around 600x and a telescope with excellent optics that can handle it.

One more tip: your attention should be focused solely on the central star and not on the Ring. The smallest telescope through which I have seen the central star was the Alvan Clark 9-inch f/12 refractor at Harvard College Observatory, using 650x with my favorite eyepiece (a 1/3-inch Fecker) that gave a field of view of only 10 feet.

The same rule applies at the other end of aperture size. Using the 1-meter f/17 Cassegrain reflector at the Pic du Midi Observatory in France, astronomical historian William Sheehan and I observed the Ring Nebula at 1,200x. The view was only of the Ring's twilight zone; the ring itself was outside our small field of view. We saw only two objects: the 14.5-magnitude central star (our estimate; other reports put it at 15.8) and its equally bright neighbor to the northwest. By comparison, the view through the 1-meter f/17 Cassegrain reflector at Lick Observatory in California was quite different because we were limited to moderately low power. The empty inner region of the Ring was filled with bright, streaky cirrus-like clouds. After a while, I was able to occasionally glimpse the central star, but it was quite difficult.

Bottom line: If you want to see the central star of the Ring Nebula, crank up the power to the limit and use eyepieces with small fields of view. Be prepared to dedicate an evening session to the challenge. Be patient. Breathe. And as always, let me know what you see or don't see at sjomeara31@gmail.com.