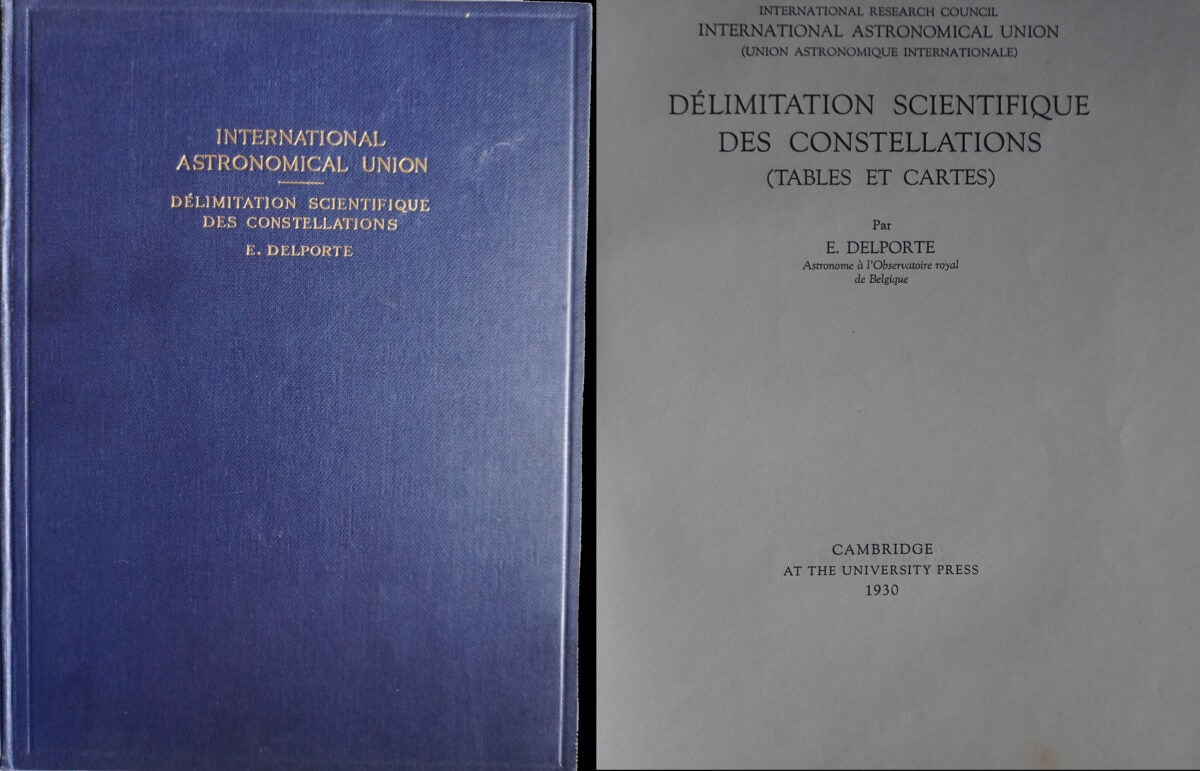

This book, Délimitation Scientifique des Constellations, written by Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte and published in 1930, established the boundaries of the 88 current constellations. Credit: Michael E. Bakich

The term “constellation” conjures up several connotations. The most well-known is “a group of stars visible to the naked eye, sometimes connected by imaginary lines or superimposed with illustrations to suggest images, whether earthly or mythological.” Strictly speaking, however, a constellation is a distinct portion of our sky with precise boundaries, not simply a collection of nearby stars as we see them.

The road to an official consensus on the issue was long, and it was not until the early twentieth century that agreement was reached. An agreement, initiated in 1922, refined in 1925, finalized in 1928, and published in 1930 by the International Astronomical Union (IAU)—the world’s leading organization of its kind—formally settled the issue, basing its solution largely on the efforts of Belgian astronomer Eugène Joseph Delporte, who mapped 88 constellations meticulously demarcated with respect to established coordinates in the sky.

Mapping the sky

Today, every astronomical object, regardless of its nature, unambiguously belongs to a specific constellation. Although the Moon and planets, which constantly move against a background of seemingly motionless stars, change their celestial direction quite frequently, we nevertheless refer to their locations within the constellations in which they are located at a given moment.

We identify the dome of the sky as half of the celestial sphere, upon which the inhabitants of the heavens are glued, the constellations themselves being infinitely deep. The lines and points projected upon it create a most convenient frame for us earthlings. In the foreseeable future, no space travel will take us far enough to justify modifying this most useful construct. Throughout history and well into the next few thousand years, the time-honored faces and ensembles were and will be there for us.

Related: Do the constellations look the same from the other planets in the solar system?

But, just as on Earth, nothing in the sky is permanent. Our view of the firmament is merely a snapshot in time. Constant, if slow, stellar change on timescales of several thousand years ensures that the seemingly eternal forms that are part of our heritage will disperse over time. However, in the absence of revisions, the boundaries of the constellations per seWith their exact sizes and contours, they will not change regardless of the movements of their residents and the resulting crossings into adjacent lands.

Creating constellations

Many early civilizations examined the stellar abode and proposed various explanations for the representations that unknown powers had placed aloft. The creation of long-lasting formations allowed nascent cultures to commemorate them with myths and legends, many of which are still known today. By emphasizing regions of dense stellar concentration and often overlooking sparsely occupied corridors, they incorporated animals and creatures, heroes and villains, and gods and goddesses relevant to the events and fables of the time.

Much like we perceive images in clouds, sometimes we need an active imagination to see what our ancestors saw. But some celestial figures — such as Orion, a towering hunter who rides conspicuously across the sky and is visible from both hemispheres between November and March — seem more credible than others. Because the range of interpretations is immense, societies have viewed the groupings differently, leading to centuries of inconsistencies in cosmic nomenclature.

Although the sky remains (relatively) static, star-related epics have evolved as their associated populations have done the same. Precursors to what we know and recognize today, the Babylonians instituted a partial basis for the constellations visible from mid- and northern latitudes, which the Greeks of the 4th century BC adopted and expanded. Forty-seven depictions from this era still stand.

The narrative begins with the rise of asterisms, star formations that we might loosely consider “protoconstellations.” Many of them (but certainly not all) have been firmly implanted in sky lore since time immemorial. Although they are not endorsed by professional astronomers, asterisms abound, and we can understand how some have been transformed into now well-defined constellations.

Asterisms can be large or small, scattered or dense, bright or faint, and they can span more than one constellation. There are no rules governing their creation—anyone can make one up, and no comprehensive list exists. Probably the best known is Ursa Major, seven bright stars within the northern constellation Ursa Major (Big Dipper). This figure is deeply embedded in our collective psyche and is often (though wrongly) thought to be a constellation in its own right.

Related: Asterisms: Find the false constellations of the night sky

In asterisms (and constellations, or any area of the sky in general) the stars have no tangible connections; they are simply in the same line of sight. Visible stars that are in the same direction as us do not normally fraternize.

The depictions of segments of the sky cultivated since ancient Babylon and Greece survived into the Middle Ages, and soon afterward empty spaces here and there were filled in. The German astronomer Johann Bayer added 11 constellations in his star atlas of 1603, Uranometrybased on observations of the southern hemisphere by explorers Pieter Dirksz Keyser and Frederick de Houtman. Johannes Hevelius, a Polish astronomer, added 10 more, seven of which have remained with us. French astronomer Nicolas Louis LaCaille generated 17 south of the equator, several of which bear the names of scientific instruments.

By the second half of the 19th century, star charts and atlases featured improvised mosaics of constellations with arbitrary boundaries of varying shapes and sizes. Many included elaborate drawings of figures superimposed on the stars, and different sources provided different delineations. However, the increasing complexity of astronomy demanded greater precision, making it necessary to refine these vague impressions of our sky.

Related: Why are constellations not always drawn the same way?

Uniformity did not come until the 1930 agreement that gave us the 88 constellations we recognize today.

Keep changing

At this point, things would be simple were it not for complications in the geometry of the sky that arise from the Earth's axial tilt of 23½° relative to the plane of its orbit. One effect of this tilt is that the Sun's apparent path in the sky as we see it, called the ecliptic, deviates over the course of a year, reaching 23½° north of the celestial equator at the beginning of summer in the Northern Hemisphere and 23½° south of the latter at the beginning of winter in the Northern Hemisphere.

Added to this is precession, the wobbling of the Earth's axis relative to the fixed astral grid (similar to the way a slowing spinning top begins to wobble and waver) on a 25,772-year cycle. As a result, the Earth's poles, while always appearing to point in the same directions, shift infinitesimally from year to year relative to the starry background. In unison, the entire celestial grid follows this slight deviation, and the lines of right ascension, declination, and the constellations move further apart. mass slightly parallel and perpendicular to each other.

Delporte drew the lines of the 88 constellations parallel and perpendicular to the position of the celestial sphere for the year 1875, which we now refer to as Epoch 1875. By 1930, the directions between right ascension and declination and the constellation lines had been repositioned to reflect 55 years of precession. Now, in 2024, 149 years of precession have passed, and current sky atlases show the lines slightly skewed relative to each other, especially near the poles.

To the extent possible, Delporte strove to keep stars within the constellations to which they had historically been assigned, but a few—such as 10 Ursae Majoris, which now resides in Lynx—sneaked through. However, Delporte’s rigorous analysis, coupled with leisurely stellar motion against the distant background, has resulted in only one of Bayer’s 1,200 stars crossing into another constellation since 1603. In 1992, Rho (ρ) Aquilae transitioned from Aquila, the Eagle, to Delphinus, the Dolphin. While numerous faint stars do cross constellation lines each year, the fact that just one example from Bayer’s 400-year inventory made the transition is a testament to the long, drawn-out timescales on which our cosmos changes—and the mere blink of an eye in which humanity has attempted to understand and map it.

Celestial taxonomy is so ingrained that labels from yesteryear are likely to persist, comparable to those still used in cities built around roads and landmarks from bygone eras. Inevitably, when the waves of stars moving into and through neighboring constellations pass a tipping point several millennia later, terminology and identifiers that depart from what we are so accustomed to today will dominate.

By then, all vestiges of the 1930 agreement will have been replaced, but for now we have a solid foundation on which to base our maps, charts and records of the sky.