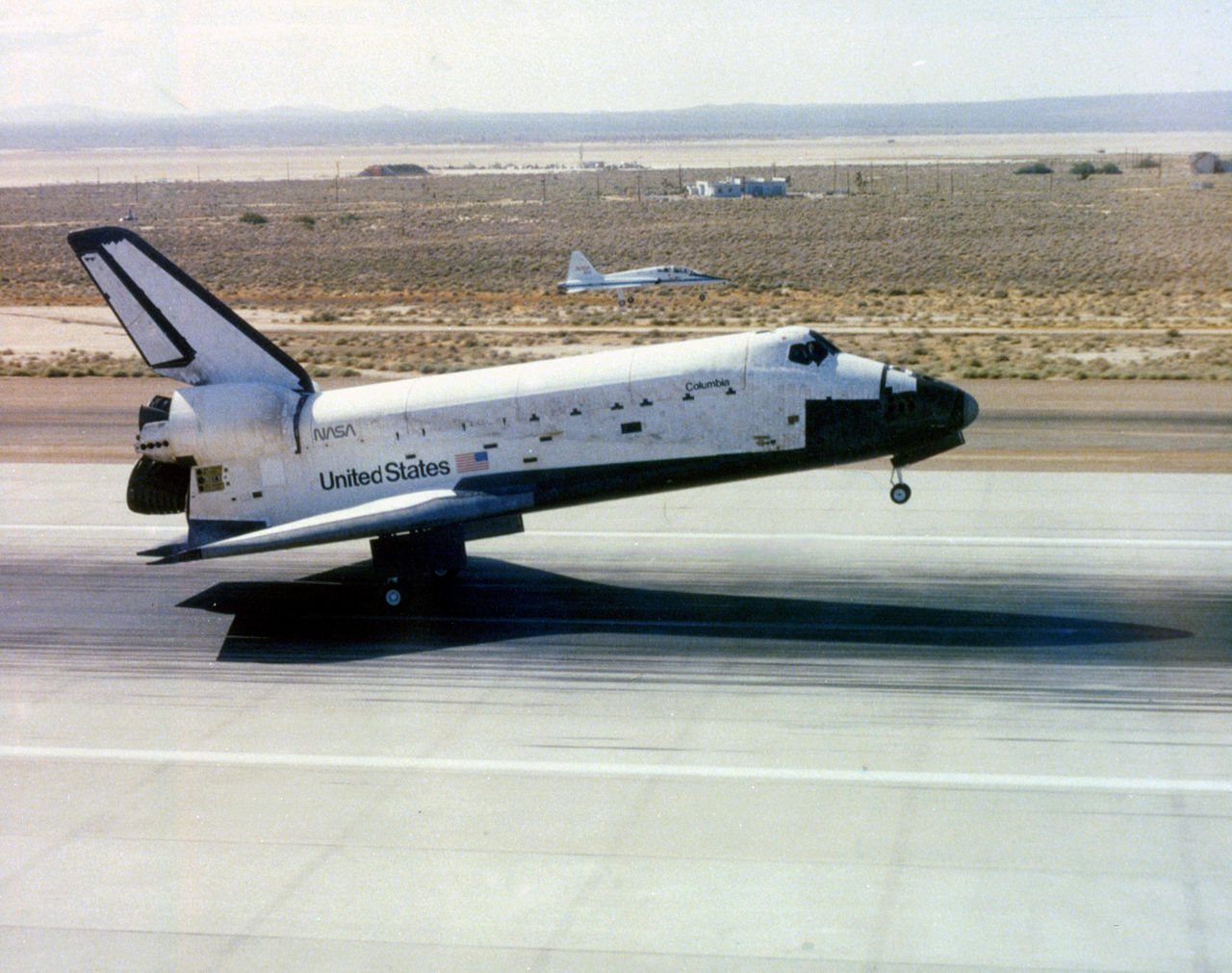

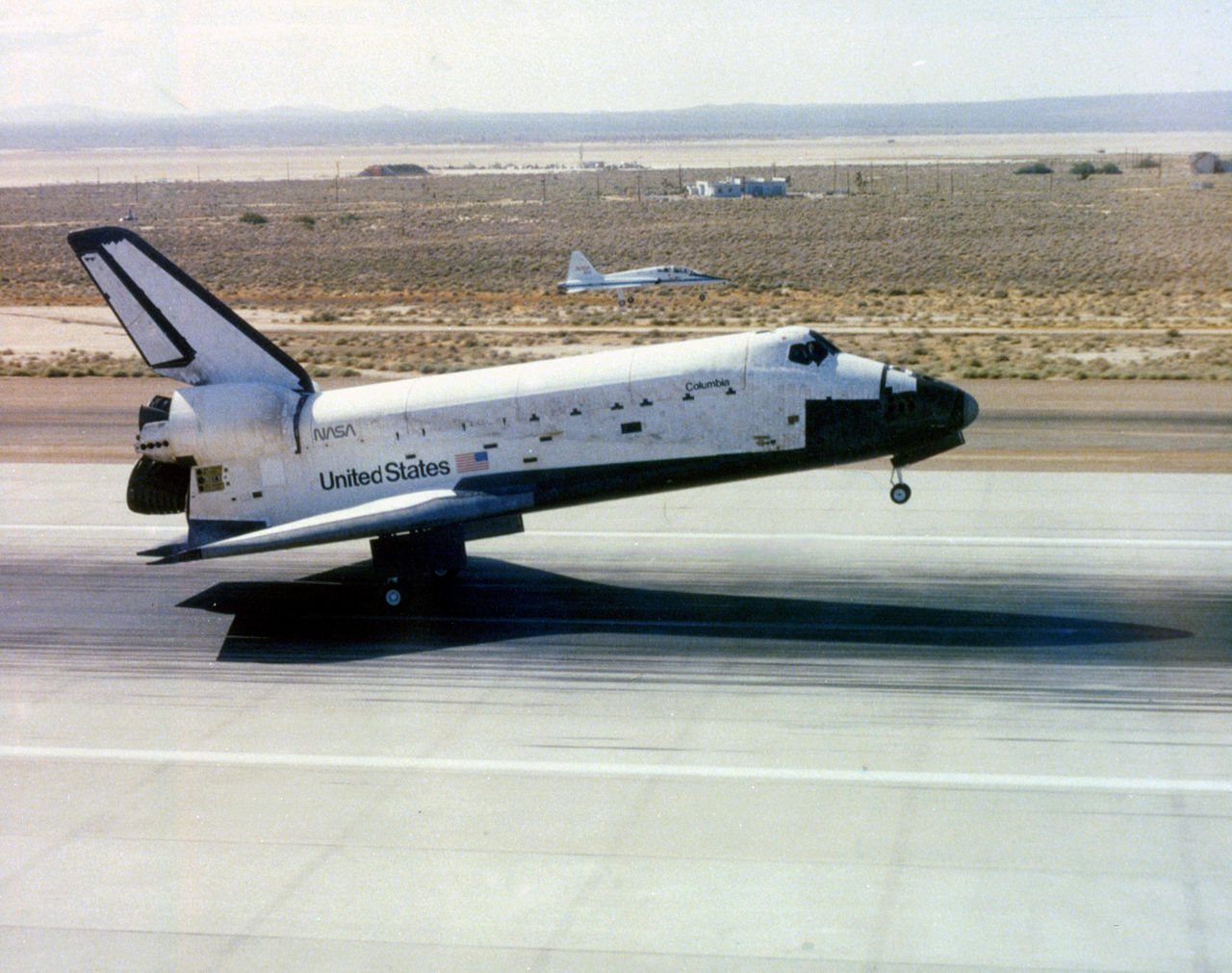

On the morning of July 4, 1982, a fast-moving black-and-white blur appeared on the horizon at Edwards Air Force Base in California, bringing a pair of American space explorers back to Earth after a week in orbit. Minutes later, at 9:09 a.m. PDT, the shuttle Columbia and its crew, Commander Ken Mattingly and pilot Hank Hartsfield— landed on concrete runway 22, becoming the first (and so far only) American human mission to land on Independence Day, America's quintessential holiday of remembrance.

Many other Americans would follow in Mattingly and Hartsfield’s footsteps aboard five more missions (including the first shuttle docking flight to Mir in 1995), and many more have since observed the day’s festivities from the lofty vantage point of Mir and the International Space Station (ISS). Only one American manned mission has ever taken off on July 4, and only one has ever landed on July 4, but the holiday has been celebrated by a succession of Americans from a far higher vantage point than the members of the Second Continental Congress could have imagined when they drafted the text of the separation of the Thirteen Colonies in 1776.

The first Independence Day that American astronauts spent in orbit began in rather comical fashion. On July 4, 1982, Mattingly and Hartsfield were in the process of packing away their research equipment. After seven days in orbit aboard the ColumbiaThe STS-4 mission had been a huge success, the last of four shuttle orbital flight tests (OFTs). Among the investigations conducted by Mattingly and Hartsfield was the first classified payload, flown on behalf of the Department of Defense.

“In one experiment, they had a classified checklist (and) because we didn’t have a secure communication link, we divided it into sections that just had letter names, like Bravo-Charlie, Tab-Charlie, Tab-Bravo, that they were to shout out,” Hartsfield recalled. Each time the astronauts spoke to U.S. Air Force controllers at the Satellite Control Facility in Sunnyvale, California, they were told, for example, “Do Tab-Charlie.”

“We had a locker where we kept all the classified material,” Hartsfield said, “and it was locked, so once we were in orbit, we opened it up and did what we had to do.” As the end of the mission neared, Hartsfield packed up the rest of the classified material and secured the locker. He told Mattingly, “I put all the classified material away. It’s all locked up.”

“Great!” Mattingly replied.

Half an hour later, Mission Control told them that military personnel at Sunnyvale wanted to speak with them. The Air Force controller asked them to “go Tab-November.”

The two astronauts looked at each other. What? hell Was it Tab-November?

Neither of them could remember. The secret nature of military training and the lack of a secure communications link also meant they could not ask by radio.

The only option was to reopen the classifieds cabinet and search through all the materials to find the checklist. Finally, after much searching, Hartsfield finally found the glossary entry for Tab-November.

He said, “Save everything and secure it.”

Mattingly and Hartsfield's arrival in the California desert was closely watched by President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan. And the crew had been informed by NASA Administrator James Beggs and were asked to think of some memorable words.

“We knew they had hyped up the STS-4 mission, so they wanted to make sure we landed on July 4,” Mattingly recalled. “There was no question that we were going to land on July 4, no matter what day we took off.

“Even if it was the fifth“We were going to land on the 4th,” he joked. “That meant that if you didn’t do any of your test missions, it was fine as long as you landed on the 4th, because the president was going to be there. We thought that was pretty interesting!”

Fortunately, Columbia's landing (the first on Edwards' concrete runway 22) occurred exactly on schedule. The shuttle touched down on the runway and Mattingly braked for 20 seconds to come to a safe stop.

Now came his great challenge: As to welcome the Reagans inside the orbiter. He and Hartsfield considered placing a notice, worded as follows: Welcome to Columbia: Thirty minutes ago, this was in space..

But things didn't go well. Just after stopping, Mattingly turned into Hartsfield.

“I’m not going to let someone come here and take me out of this chair,” she said. “I’m going to give it all the strength I have and get up on my own.”

Previous crews had returned to Earth, some feeling fine, some nauseous, and still more needing a stretcher to get them out of the spacecraft for medical attention. That wouldn't be possible, and Could not—to happen with the president present.

Mentally and physically prepared to meet his commanding officer, Mattingly rose from his seat to disembark…and promptly hit his head on the overhead instrument panel. thatHartsfield joked, “it's very graceful!”

The two returning heroes pulled themselves together, and Mattingly cleaned up some blood stains. In the minutes before the shuttle hatch opened, they reunited with their “Earth legs” and then headed down the stairs to meet the Reagans.

Hartsfield, known for his ruthless sense of humor, was in top form that day. “If you do the same thing you did getting out of the chair, you’re going to walk down the stairs and fall, so you need to have something to say,” he told Mattingly.

“Why don't you look at the president and say: “Mr. President, those Are these shoes beautiful? Do you think you can do it well?

Mattingly stared at him.

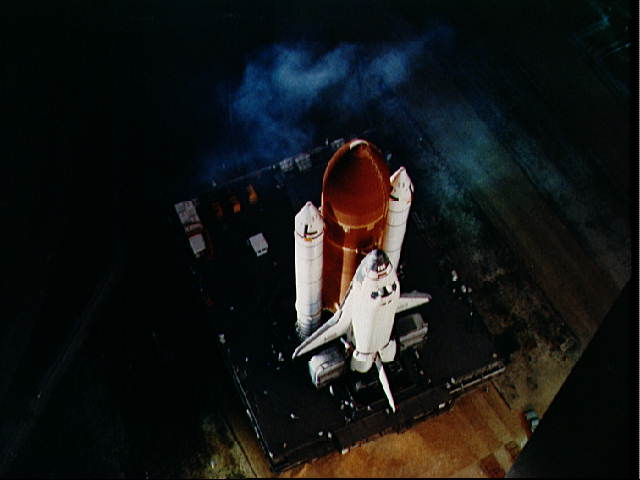

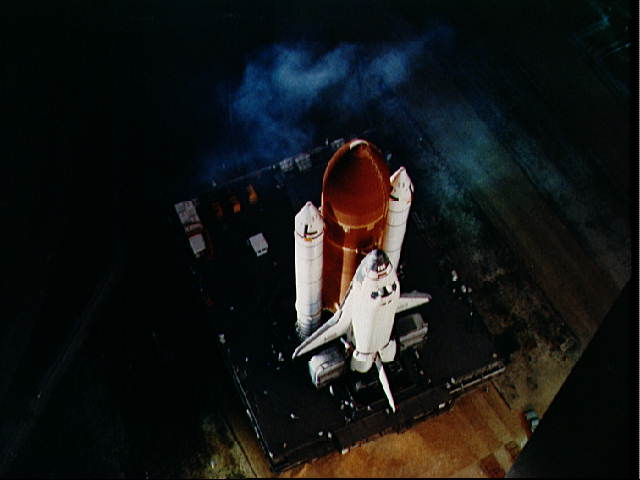

Twenty-four years later, on July 4, 2006, Discovery inadvertently became the only U.S. crewed space mission to launch on Independence Day. Aboard the shuttle that day, STS-121 Commander Steve Lindsey, Pilot Mark Kelly, and Mission Specialists Mike Fossum, Lisa Nowak, Stephanie Wilson, and Piers Sellers were flying the second return-to-flight test mission to the ISS. Following the tragic loss of the Columbia in February 2003.

They were also ferrying German astronaut Thomas Reiter up the hill for the European Space Agency's (ESA) first extended stay on the station. As they emerged from their quarters that morning, Lindsey's crew waved American flags, with the exception of Reiter, who waved a German tricolor flag. “I don't know if it was the German Fourth of July or not,” Lindsey joked at the post-flight news conference.

Without further ado, they launched into the crystal-clear Florida sky at 2:55 p.m. EDT. “And off the space shuttle Discovery lifted off,” the launch announcer gushed, “returning to the space station, paving the way for future missions beyond.”

Those missions will no doubt see a future American crew take off or land on Independence Day, though so far the exploits of Mattingly and Hartsfield in 1982 and Lindsey have been remembered and others. There were no repeats of this in 2006. That said, four other shuttle crews were in space during the holiday, including Columbia. STS-50 in 1992 and STS-78 in 1996Both set records for the longest shuttle flight, as well as STS-71 in 1995the first docking mission to the Russian space station Mir, and STS-94 in 1997.

Three other American astronauts — Norm Thagard, Shannon Lucid and Mike Foale — celebrated aboard Mir during its long ascents in 1995, 1996 and 1997. And since 2001, there has been an American presence on the ISS for every Independence Day. That year, Jim Voss and Susan Helms became the first Americans to celebrate the Fourth of July from the ISS.

And in 2010, for the first time, three American astronauts — Tracy Caldwell-Dyson, Doug Wheelock and Shannon Walker — observed the holiday from the massive orbital complex. Among later occupants of the International Space Station to take part in Independence Day was Chris Cassidy, who ran a “Four on the Fourth” road race on the space station’s treadmill in 2013, while his crewmate Karen Nyberg presented cookies she had frosted in the colors of the American flag.

This year, with Expedition 71's Matt Dominick, Mike Barratt, Jeanette Epps and Tracy Dyson, plus Starliner Crew Flight Test (CFT) astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Suni Williams, aboard the ISS for the holiday, more Americans have been in space on Independence Day than at any time since STS-121 in July 2006. And with Artemis missions with human transport on the horizonIt won't be many more years before America's day of reflection is celebrated from the surface of the Moon and, eventually, Mars.

Leave feedback about this