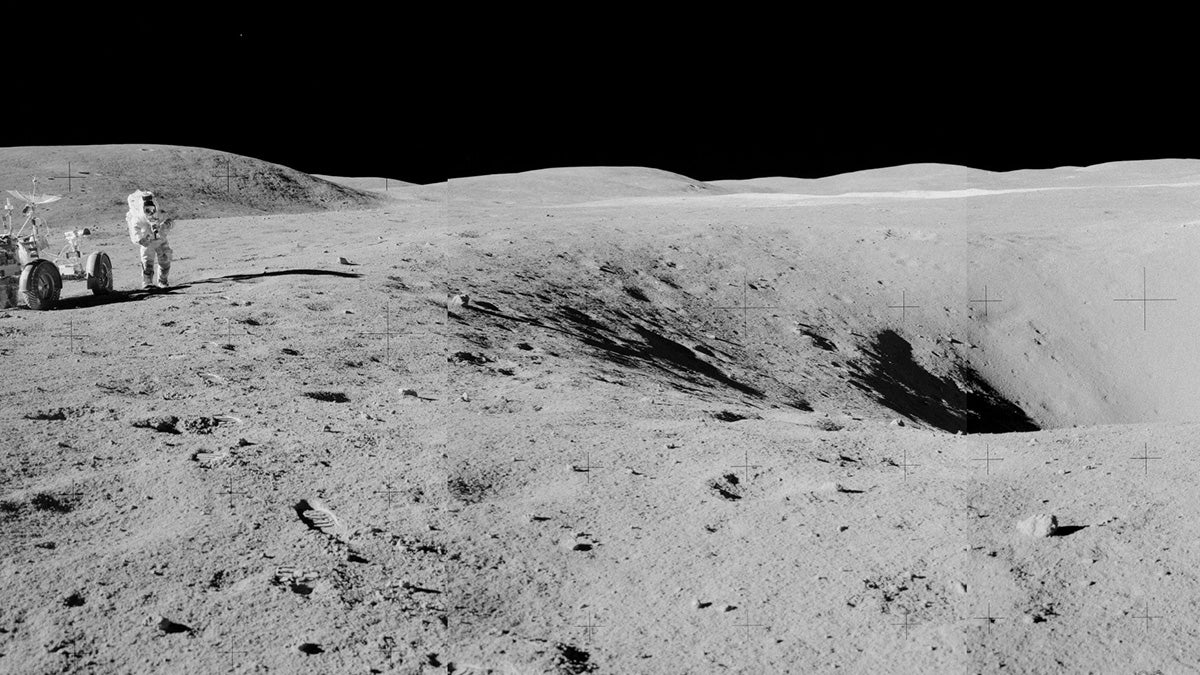

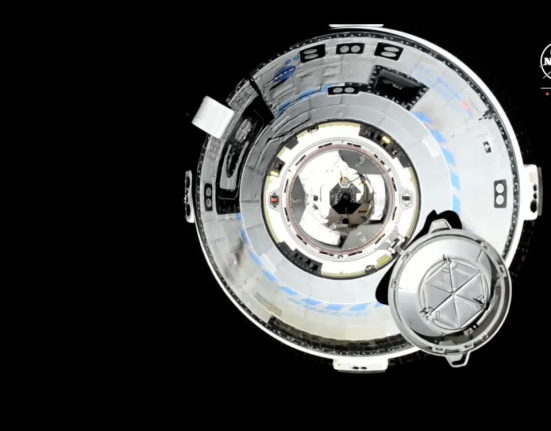

Big Muley, the largest sample brought back by the Apollo program, is seen just above the right extension of astronaut John Young’s shadow on the left of this image. A new analysis of Big Muley and other Apollo moon rocks shows that the Moon’s magnetic field was limited to its early history — possibly only 140 million years — and died before the rocks crystallized. Credit: NASA

Our Earth is about 4.5 billion years old, and through painstaking work, scientists have managed to piece together a timeline of its past. But much of its earliest history remains a mystery. Little geological evidence remains from the first 500 million years, an elusive era when our planet was a ball of molten rock routinely bombarded by large asteroids. These were powerful enough to evaporate any pockets of water and crust-forming rocks, making it impossible for any kind of life to emerge. That turbulent period of time is called the Hadean Eon, after Hades, the Greek translation of “hell.”

It’s not clear how our planet went from such a harsh environment to the habitable orb we occupy today. But researchers are looking for ways to uncover clues about this transformation. “Earth’s early atmosphere is all about the evolution of a habitable planet,” says John Tarduno, a professor of Earth and environmental sciences at the University of Rochester in New York.

However, he admits, “trying to discover what the Earth’s primitive atmosphere was like is a big challenge.”

The key to overcoming part of that challenge could be traces of Earth's most primitive air, long ago stuck on the Moon's surface. And those traces may be tantalizingly close at hand. Upcoming NASA Artemis Missionssuggests a new study published by Tarduno and colleagues earlier this month in the journal Earth and Environment Communications.

Pieces of air

It may seem unlikely that the Moon would be a place where remnants of Earth’s atmosphere would be found, but satellite observations show that such transfers are a regular occurrence. For about five days each month, the Moon floats through Earth’s vast magnetosphere, picking up trapped atmospheric molecules that come its way. Those molecules easily stick to the Moon’s surface, thanks to its lack of a magnetic field, which would otherwise protect the surface by repelling material.

According to a new analysis of lunar rocks brought back by Apollo astronauts about 50 years ago, this transfer of atmospheric material from Earth may have occurred as early as its enigmatic Hadean period. The 4.36 billion-year-old rocks reveal no conclusive evidence that they were oriented by a magnetic field, suggesting that the Moon's dynamo (a molten core that, when spinning, can produce a magnetic field) died before the rocks crystallized… Yeah Did the Moon ever have such a dynamo? (Scientists are still not sure.)

“We think the absence of a magnetic field is really exciting,” Tarduno says. That’s because the lack of a magnetic field means that any portion of our Hadean-era atmosphere that might have floated toward the Moon would have stuck to the surface in a similar way and could still be buried in lunar regolith, he says.

Unlike Earth's landscapes, which are constantly being recycled, the Moon is geologically quiescent, so any remnants of our planet's Hadean atmosphere that reached the lunar surface would have remained intact for billions of years, the study found.

“In theory, some Hadean atmospheric components may remain in ancient lunar regolith accessible in the Artemis Exploration Zone,” said David Kring, a senior scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Texas, who was not involved in the new paper. “However, any such clues will be fragmentary and difficult to interpret.”

Hopes that the sample will return

If Artemis sample return missions could locate places on the Moon with ancient rocks, “you could get direct measurements of what’s happening in Earth’s atmosphere,” Tarduno says. For example, there are craters that harbor ancient regolith protected between lava flows of two different ages, which could serve as a reference for scientists to date that regolith more precisely than anywhere else on the Moon. Extracting fragments of those precious reserves from the Moon’s surface “would require a complicated setup, but it’s not far-fetched,” Tarduno says. “It’s really about finding the best place to do it.”

Additionally, he says, it will be difficult to prevent certain illuminating gases from escaping from the regolith while drilling for samples, but “these things are not insurmountable,” he adds.

The Artemis missions could also shed light on other aspects of Earth's early history, and perhaps even help scientists answer the decades-old paradox of why our planet's water… No Earth froze over about 4.5 billion years ago, under the reign of the then-young Sun, which shone 30 percent dimmer than it does now. By 4.4 billion years ago, however, our planet was home to liquid water, quickly followed by nascent life, leaving scientists to ask fundamental questions about the habitability of our early planet.

The answer to those questions could be somewhere on the Moon awaiting our visit.

“It’s an exciting time,” Tarduno says.

Leave feedback about this