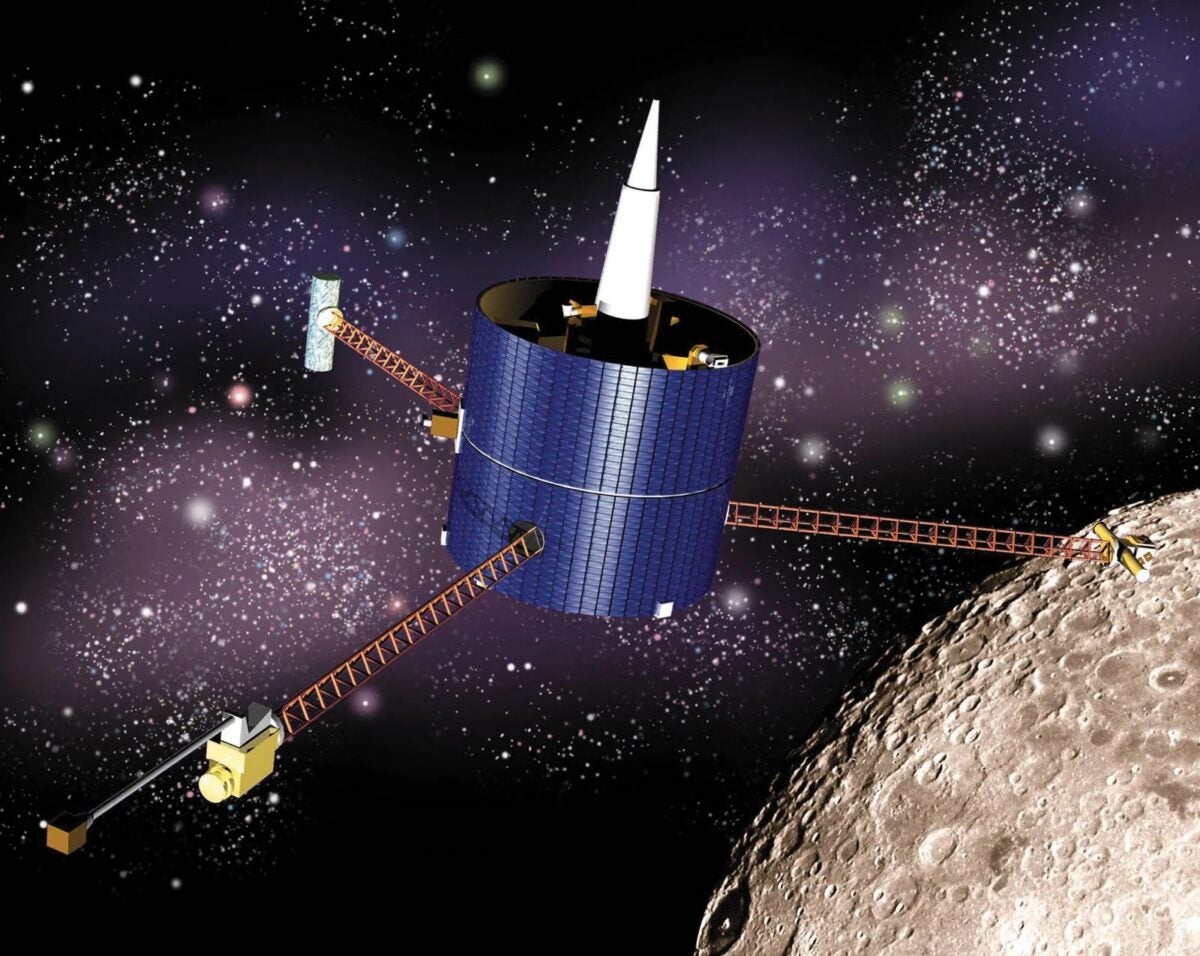

Artist's rendering of the Lunar Prospector space probe. (Credit: NASA/JPL)

On July 31, 1999, human eyes were fixed with great excitement on the Moon's south pole as a spacecraft hurtled toward its destination in an astonishing attempt to discover traces of water on a parched world. Although the Lunar Prospector probe quickly died in a dark crater, it sparked a search for the building blocks of life on our celestial neighbor for years to come.

Its 18-month journey to Earth’s only satellite uncovered a site with the potential to hold colossal reserves of water ice at its poles, hinted at an iron-rich core and located a paltry magnetic field. “A journey to rediscover the Moon,” was how NASA commentator George Diller described it as Lunar Prospector blasted off into the darkness over Cape Canaveral, Florida, aboard an Athena II rocket at 9:28 p.m. EST on Jan. 6, 1998.

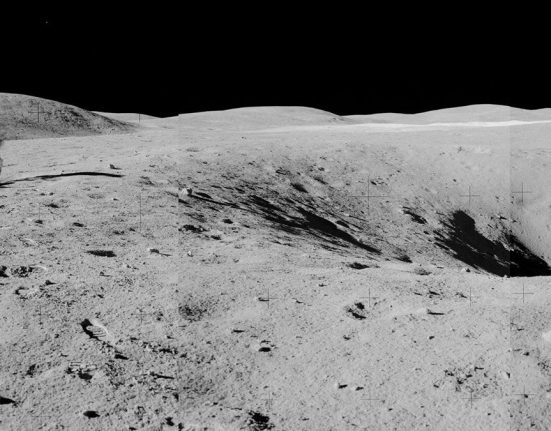

Diller was right. More than two decades after the last man left his footprints in the lunar dust, the Moon's uniqueness was widely acknowledged, but its lack of geological life was taken for granted. But when Apollo astronauts forever altered the image of the Moon, the Lunar Prospector spacecraft would do so again.

Mission plans

Lunar Prospector emerged from the drawing board of NASA’s low-cost Discovery Program, a drive to explore space with missions priced at less than $150 million — a fraction of multibillion-dollar flagship projects like the Viking probes at Mars, the Galileo orbiter at Jupiter, and Voyager’s half-century-old grand tour of the outer solar system. Lunar Prospector’s final price tag was a comfortable $62.8 million.

The project, which began development in 1995, aimed to launch a polar-orbiting mission in 1997 to map the composition of the Moon's surface, assess possible water-ice deposits, and characterize its magnetic and gravitational fields. Built by Lockheed Martin, the drum-shaped probe was equipped with three equidistantly spaced instrument arms, each measuring 2.5 meters (8 feet) long.

Six instruments—an electron reflectometer, a magnetometer, a gamma-ray spectrometer, a neutron spectrometer, an alpha particle spectrometer, and a Doppler gravity experiment—would globally explore a world whose 14.6 million square miles (38 million square kilometers) equals a total land area slightly smaller than that of Asia.

Before Lunar Prospector, less than 25 percent of the Moon had been mapped in detail, and key questions about its origin and evolution were a blank slate.

But hopes for a mid-1997 launch evaporated due to development problems. Further technical problems with the Athena II rocket delayed the launch until January 1998.

After liftoff, Lunar Prospector took 105 hours (about four and a half days) to travel the 370,000 kilometers (230,000 miles) from Earth to the Moon. On January 11, it entered an initial “capture” orbit. It then gradually reduced its orbital period from 11.6 hours to just under 2 (118 minutes, to be exact) before entering a polar “mapping” orbit that brought it just 100 kilometers (62 miles) above the rugged lunar terrain.

A year of discoveries and surprises had begun.

H Identification2Oh

In March 1998, Lunar Prospector had already tentatively identified water ice in permanently shadowed craters near the north and south poles. It did so by revealing a substantial amount of hydrogen, which was thought to be locked up in water. The water signature was 15 percent stronger at the north pole than at the south. Hydrogen concentrations at the poles were also three times higher than the lunar average.

Early calculations estimated that about 300 million metric tons of water ice were trapped in rock at the poles, but were later revised in September of that year to 6 billion metric tons, buried in highly concentrated deposits beneath 18 inches (45 centimeters) of lunar regolith.

Crater floors in permanent shadow never face the Sun, and remain dark in some cases for more than 2 billion years. They are usually located at high latitudes where the Moon's axis is nearly perpendicular to the direction of sunlight.

One of these craters, called Shoemaker, is 20 miles (32 kilometers) wide and lies east of the lunar south pole at 88.1 degrees south latitude. Its age is evident in a badly worn rim and dozens of small craters that mark its interior walls. Eternally dark, conditions at its bottom never rise above -173 degrees Celsius (-343 degrees Fahrenheit).

At its deepest point, Shoemaker reaches 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles) deep, deep enough to stack three skyscrapers the height of Dubai's Burj Khalifa. At these depths, so-called cold traps form on its dark bottom, where water molecules from comets or other impacting objects accumulate and remain indefinitely.

With significant amounts of hydrogen and water ice at both poles, the evidence was compelling that the Moon could support human colonies. “The data don’t tell us definitively what form the water ice is,” said Lunar Prospector principal investigator Alan Binder. “However, if the primary source is comet impacts … our explanation is that we have areas at both poles with layers of nearly pure water ice.”

A deep dive

Lunar Prospector completed its year-long baseline mission in January 1999 and was then extended for m months. Its orbit was lowered to 25 miles (40 km) above the surface to collect higher-resolution data, then lowered again to 9.3 miles (15 km).

As its mission neared its end, a novel plan was hatched under which NASA would crash the probe into a permanently shadowed crater to test the hypothesis that there was indeed water ice beneath the surface. When the probe crashed, researchers reasoned, the buried water ice might be ejected into space and visible in the resulting plume. Shoemaker proved an ideal candidate: Its rim was high enough to be permanently shadowed, but low enough that Lunar Prospector could plot an approach and impact trajectory, striking the crater floor with near-perfect accuracy.

The mission's end and destination had even greater significance, as aboard Lunar Prospector were the ashes of geologist Eugene Shoemaker, the crater's namesake.

Although the odds of drilling a hole deep enough into Shoemaker's floor to release a rich plume of water ice were estimated at no more than 10 percent, the daring dive captivated an earthly audience and grabbed international headlines.

At 4:52 AM EDT on July 31, 1999, the Lunar Prospector spacecraft struck the crater at 6,100 km/h (3,800 mph), causing the shortest flash ever seen from Earth. Unfortunately, no water was detected, possibly because the spacecraft missed its target, struck a rock, or simply hit a patch of dry land.

Despite the lack of results, scientists are not discouraged from trying again. In October 2009, the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) reached Cabeus, a south polar crater, and this time managed to reveal grains of water ice in the ejecta. Later, data from NASA's Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3), aboard the Indian Chandrayaan-1 probe, confirmed that there are patches of water ice in many permanently shadowed craters. And in late 2024, NASA's PRIME mission will drill for ice in Shackleton Crater, which is located near Shoemaker at the lunar south pole.

This renewed interest in our closest celestial companion is largely due to Lunar Prospector. Its short but eventful life tempted us with the lure of water on a world once thought to be lifeless. And the Moon’s power over humanity continues to resonate a quarter-century later, as we prepare for our next great adventure: returning to the lunar surface to stay.

Leave feedback about this