In another 3.75 billion years, the Andromeda Galaxy (left) will loom large in Earth's skies, as shown in this illustration. By then, the massive galaxy's gravity will have begun to distort the plane of our Milky Way, at right. Credit: NASA; THAT; Z. Levay and R. van der Marel, STScI; T. Hallas; and A. Mellinger

If you've ever attended a star party, it's more than likely that the astronomer present pointed to the Andromeda galaxy (M31), currently about 2.5 million light years away, and mentioned that it is expected to collide with the Milky Way in about 4.5 billion years. But recently, an international team of astronomers published a study on the arXiv preprint server claiming that the merger of the two galaxies is far from guaranteed.

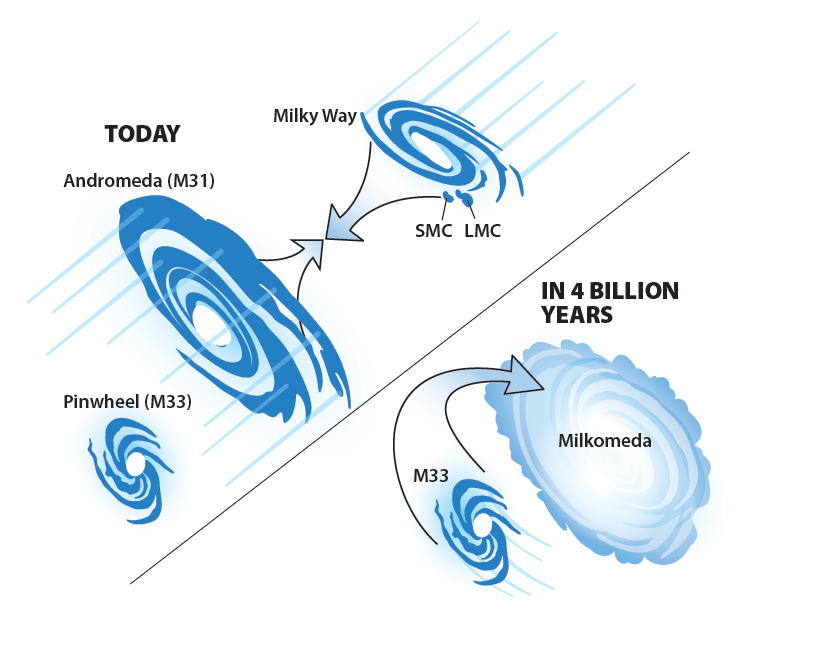

The team, led by Till Sawala of the University of Helsinki, ran simulations that included four of the world's largest galaxies. local group: Andromeda, the Milky Way, the Triangle Galaxy (M33) and the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC). Each combination of the multibody system produced different results for the fusion. The data comes from the most up-to-date measurements of each galaxy's mass and proper motions made by Gaia and the Hubble Space Telescope.

not so fast

Before Edwin Hubble determined that Andromeda was far outside the Milky Way and was a galaxy in its own right, it was one of many so-called spiral nebulae that were believed to lie within the Milky Way. But even before this discovery, astronomers had already realized that Andromeda was approaching us. Since then, enormous efforts have been made to produce the most precise measurements of the galaxy's properties and, in recent decades, to develop computer models to predict its titanic collision with our galaxy. Some say the first close encounter will occur in less than four billion years, while others say it will be after 4.5 billion years. But over the last decade or so, the consensus has leaned overwhelmingly toward collapse being inevitable.

Related: The date of our galaxy with destruction.

Not so fast, says Sawala's group. The probability of the collision occurring (resulting in an elliptical galaxy called Milkomeda) varies greatly depending on the inclusion or exclusion of any of the other two Local Group galaxies mentioned above.

The researchers chose to use a simulation developed by the Institute for Computational Cosmology at Durham University in England. The galaxies residing in the Local Group are gravitationally bound, so apart from the individual parameters of each member, the model must also include gravitational forces and dynamical friction: the transfer of energy through gravitational interactions, which is the factor dominant as the collision approaches and leads to the decay of galactic orbits. However, it's important to note that even the “most precise” measurements still have a wide range of uncertainty, so the team used a method known as Monte Carlo sampling to test tens of thousands of possibilities within those uncertainties.

It's this range of uncertainty, compounded by the inclusion of four different galaxies, that led Sawala's group to raise a yellow flag about Milkomeda's future.

Every little bit counts

Sawala's team first ran the model with just the Milky Way and Andromeda, with masses of one trillion and 1.3 trillion solar masses, respectively. It showed that the two galaxies merged in less than half of the cases, mainly during the second closest encounter. And depending on the proximity of that encounter, the moment of collision would be 7,600 or eight billion years from now. “Based on the best current data, both outcomes are almost equally likely,” the study stated.

To up the ante, they used a three-body system, including the Triangulum galaxy, and found that this increased the chances of collision to about two-thirds in a similar time period as the two-body system. The model showed that M33 slowed down Andromeda's speed relative to our galaxy, meaning Andromeda was not moving away fast enough to avoid merging.

But adding the LMC changed things once again, with or without the M33. Simulating just the Milky Way, Andromeda and the LMC resulted in mergers in only a third of all cases. But when all four galaxies were included in the model, the collision rate increased again to a coin toss that occurred over the next 10 billion years.

Gravity and time will tell

Uncertainty is the most important factor in, well, uncertainty. The mass of the Milky Way is only known to within about 20 percent, and it is only known to within 30 percent for the two smaller galaxies. Furthermore, while the individual contributions of the smallest members of the local group of galaxies are almost negligible, they are not when taken together, and calculating that effect is a daunting computational task, one that has not yet been covered by the team. Sawala.

Weighing entire galaxies (their stars, dust, and invisible dark matter) and measuring their motions is a basic but still monumental task in astronomy. Gaia's fourth data release, expected in 2026, along with other new or updated surveys will help, but only to a point.

By unfolding possibilities across eons of future time, even small ripples in the cosmic current can have large effects. The only way to know for sure might be to wait 10 billion years.

Leave feedback about this