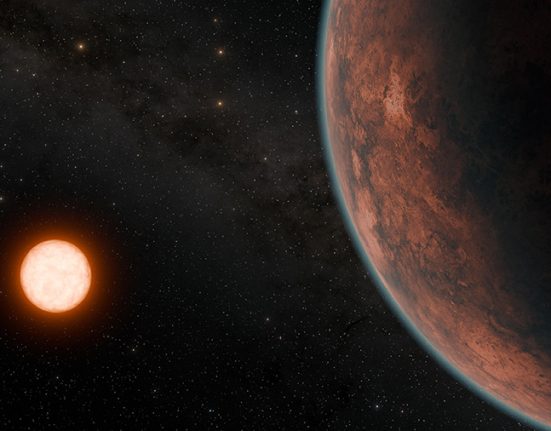

The ethereal glow of the northern lights, a highly sought-after sight on Earth, has now been found on a giant world many times the mass of Jupiter, astronomers announced at this week's meeting of the American Astronomical Society in New Orleans.

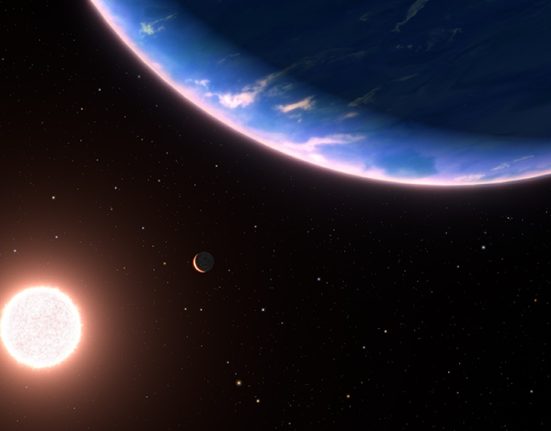

NASA, ESA, CSA and L. Hustak (STScI)

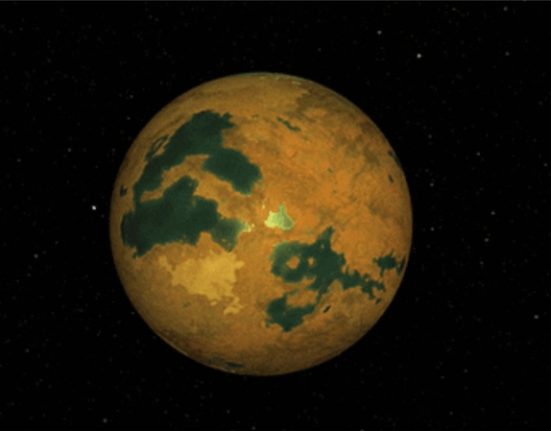

This finding itself is not that unusual, since charged particles from the Sun, as well as Jupiter's volcanic moon Io, create auroras on many planets in the solar system. Therefore, it is not surprising that this world, called W1935, may exhibit the same phenomenon. Only, in this case, the world is far from any star.

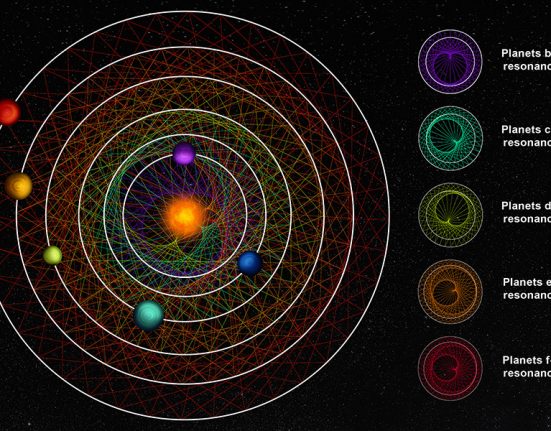

Jackie Faherty (American Museum of Natural History) encountered this world when she and her team spent time on the James Webb Space Telescope to examine the atmospheres of 12 of the coldest brown dwarfs. Brown dwarfs are worlds more massive than Jupiter, but not massive enough to sustain nuclear fusion in their cores. So as they get older, they get colder. The coldest brown dwarfs are therefore either the oldest, the smallest, or both. But the coldest brown dwarfs are also the most difficult to see, since they are out of reach of ground-based telescopes and just within reach of JWST. (For context, these brown dwarfs are still pretty hot at 400ºF, about the right temperature for baking cookies.)

Of the 12 brown dwarfs Faherty's team investigated, one jumped. Citizen scientist and participant in the backyard worlds The Dan Caselden project discovered the so-called W1935 as a faint fuzz moving against the background stars. With JWST's sensitive instruments, that faint fuzz was turned into an intricate infrared spectrum, revealing a world of chemistry and an unexpected feature.

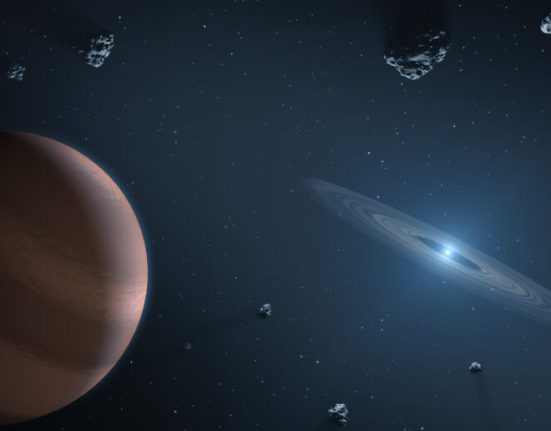

NASA, ESA, CSA and L. Hustak (STScI)

Revealing the spectrum, Faherty noted: “Every movement you see here is real, a real molecule that is absorbing light.” But in the midst of those wiggles, one defied explanation. “It was like a pebble in a shoe that I couldn't get rid of,” Faherty says.

At wavelengths shorter than about 4 microns, the methane molecule absorbs most of the light. But in the middle of the methane absorption there was a bump, which Faherty's team eventually discovered was methane in issue. To be detected in emission, the responsible gas would have to be hotter than the 400ºF brown dwarf; in other words, the auroras.

Auroras require two things: a strong magnetic field, which a brown dwarf can generate if it spins fast enough. But they also require hot ionized gas or plasma. W1935 is an isolated brown dwarf, far from any host star, so where does the plasma come from?

Faherty doesn't know either, but he has ideas. One of them, and perhaps the most attractive, is a geologically active moon, like Jupiter's Io. Io's volcanoes generate charged particles that then escape the moon's gravity and are captured in Jupiter's magnetic field. Similarly, on Saturn, Enceladus's icy water geysers generate charged particles that contribute to the ringed planet's lights.

Other possibilities are no less intriguing. The planet could have encountered a “burp” of plasma in the space between the stars, left by some forming object. In that case, future JWST observations could show that the auroras in W1935 disappear as the particle source dissipates.

Auroras may even shed some light on what's happening in our own solar system. Although the giant planets have the Sun and active moons as a source of plasma, the auroras they generate are nevertheless brighter than expected.

“Frankly, I feel like I've walked into a drama that's happening in the solar system,” Faherty says. “Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune also have too much energy in their upper atmospheres.” However, he adds that one of the main explanations for this (that gravity waves inside the planets are pumping energy to the outer layers) doesn't work for W1935, because the world only shows emissions of methane, not other gases. .

While W1935 is too faint for any kind of ground-based monitoring, the team intends to ask Webb for additional observations of the brown dwarf. Perhaps future data will show that the auroral emission varies in intensity or disappears, or perhaps a moon could even be revealed by its gravitational pull.

Leave feedback about this