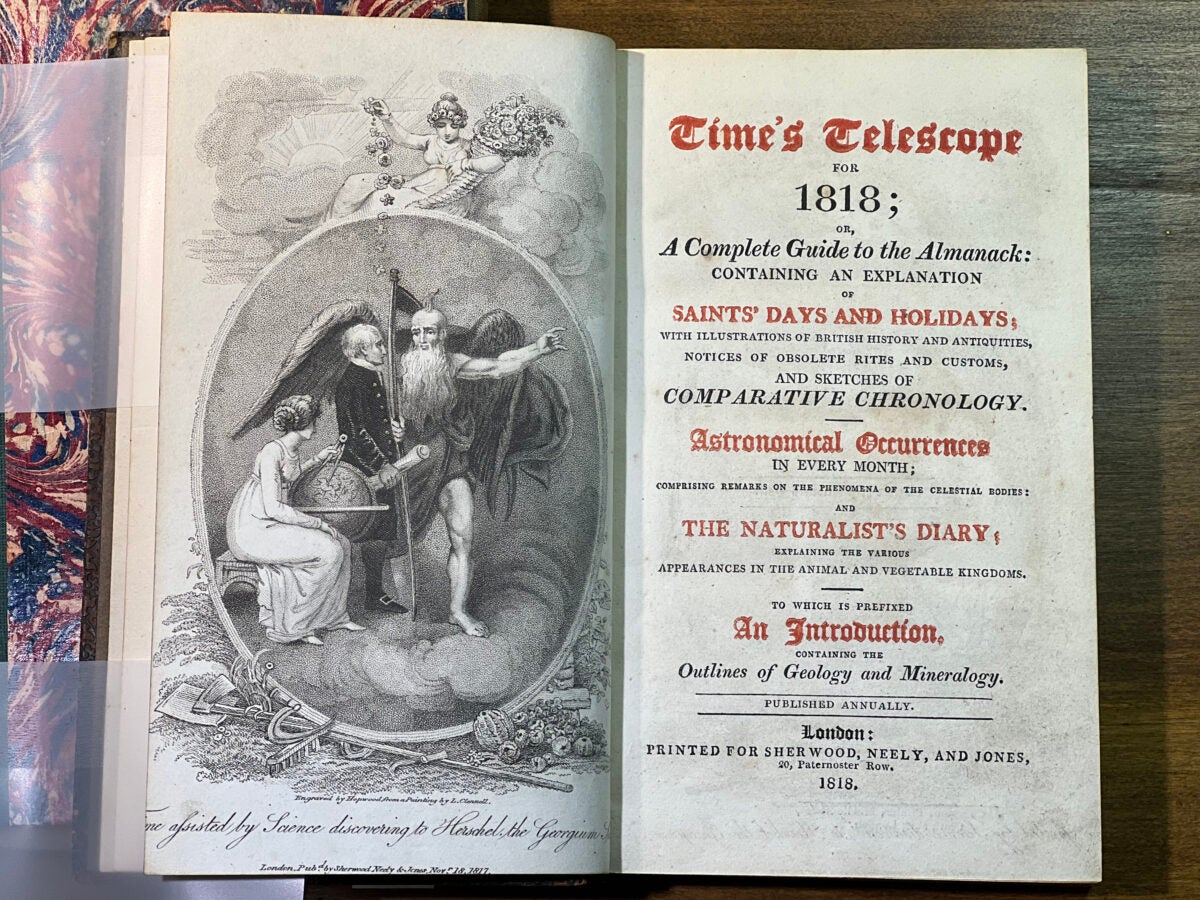

E: The Time Telescope was an almanac published in London between 1814 and 1834. Credit: Raymond Shubinski

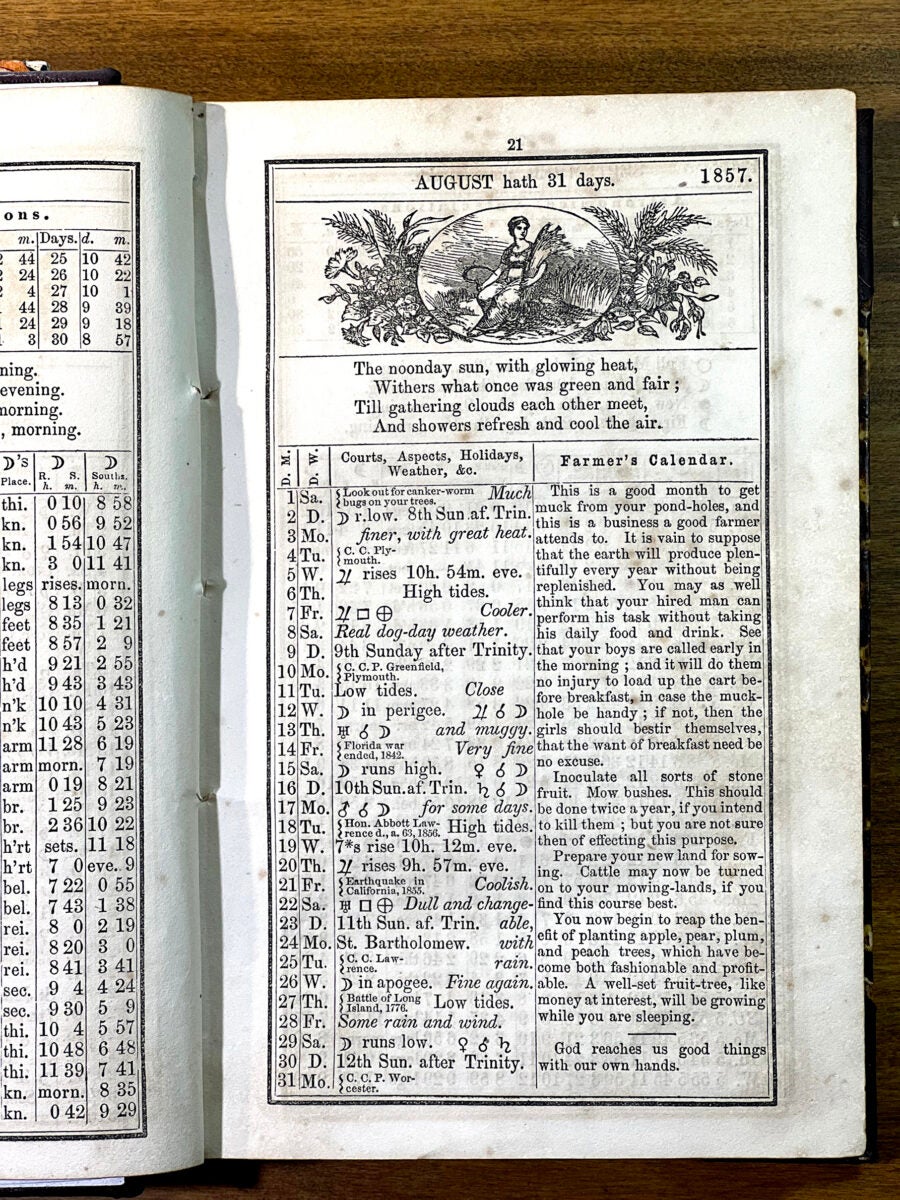

Every September, almanacs begin appearing all over the United States. The most well-known is The Old Farmer's Almanac, which has been in print since 1792. Its cover claims it is “useful, with a pleasant degree of humor,” and the little book is packed with astronomical information, weather predictions, and much more.

The United States government is also in the almanac business, and has been for over 150 years. Its publications include The Nautical Almanac, The Air Almanac, and The Astronomical Almanac.

The U.S. Naval Observatory’s Astronomical Applications Department website notes: “Scientific research, timekeeping, calendars, and navigation have depended on the practical skills of positional astronomy for thousands of years.” Today, astronomical almanacs provide the positions of the Sun, Moon, and planets. They guide automatic telescopes, set planetariums, and aid in navigation.

Early almanacs

For centuries, astronomers produced these almanacs through painstaking calculations. The process was difficult, and the resulting publications were often plagued by errors due to faulty instruments and poor observational skills.

The basic format of modern almanacs was formed in Europe during the Middle Ages. Almanacs of saints' days, church celebrations, and Easter dates were produced by monasteries. The books provided practical information for everyday life and included the positions of the Moon and planets.

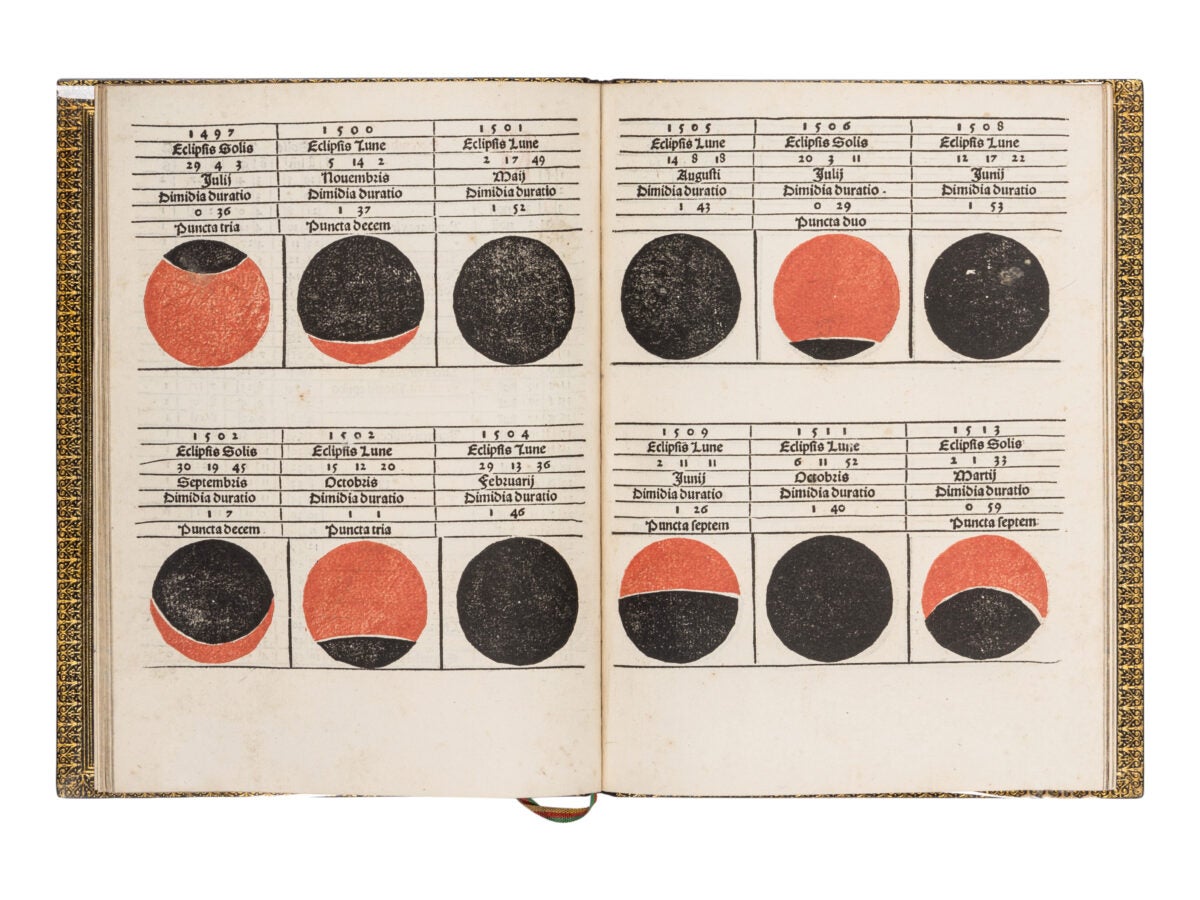

But the first true astronomical almanac was produced in the 15th century by Johannes Müller von Königsberg. Better known as Regiomontanus, the mathematician and astrologer produced his most important work in 1474: the Calendarium and Ephemerides. At over 700 pages, the massive almanac contained predictions of lunar and solar eclipses, positions of stars and planets, and even usable paper astronomical instruments.

Regiomontanus' almanac was intended for astrologers, but its astronomical data proved very useful to sailors. On his fourth voyage to the Americas, Christopher Columbus had to run his ships aground in Jamaica. The indigenous people provided him with food, but after six months, they grew fed up with the crew's demands. Facing famine, Columbus consulted his copy of the Calendarium, which predicted a total lunar eclipse on the night of February 29, 1504. Columbus threatened to light the Moon if the locals did not cooperate. That night, the Moon rose and turned blood red, demonstrating the “power” of Columbus and his God, and saving the Europeans.

Growth in Britain and the United States

In 1766, Britain commissioned the creation of the first Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris. Since the early 18th century, the nation had been in a race to develop an accurate method for determining longitude at sea. In 1714, Parliament offered a prize of £20,000 to anyone who could come up with a “plain and practical method for the accurate determination of the longitude of a ship at sea.”

Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne was a proponent of the lunar distance method, which involved measuring the angular separation between the Moon and a bright star and comparing the observation with an almanac based on Greenwich Mean Time. The key was an almanac that gave accurate positions of the Moon and bright stars.

While astronomers produced ever more accurate almanacs for navigation, there was also a need for information to aid farmers, merchants, and others. As a result, publishers throughout Europe began producing an increasing number of almanacs. They ranged from books with just a few pages to leather-bound volumes. By the early 19th century, these almanacs became indispensable.

Across the pond, the first colonial almanac, An Almanac for New England for the Year 1639, was written by William Pierce and printed at Harvard College. But Poor Richard's Almanack, written and printed by Benjamin Franklin, is arguably the most famous American almanac. He may have gotten the idea for it while living in London, where he no doubt saw Rider's British Merlin, a volume published in England as early as 1656.

Another important almanac was that of Benjamin Banneker, who was born a free African American in 1731. He was a brilliant self-educated man, famous for having surveyed what would later become the District of Columbia. He was also deeply interested in astronomy and successfully predicted a solar eclipse in 1789. This may have inspired him to print the Almanac and Ephemeris of Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia from 1792 to 1797.

The gold standard

The Old Farmer's Almanac and others of its kind provide a lot of astronomical information, but astronomers need more.

Publication of the English Nautical Almanac began in 1767 in response to the need for greater accuracy in navigation. The American Nautical Almanac and Ephemeris appeared in 1855 and continued until 1980. In 1981, the United States and England joined forces to publish a single book, the Astronomical Almanac.

Most observatories and planetariums have a copy of the Astronomical Almanac on hand or an online subscription to its contents. The amount of information it contains is astounding—more than most people need about every aspect of astronomy.

Other astronomical almanacs are more useful for amateurs. One of the best is the Observer's Handbook, published by the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. It contains similar information to The Astronomical Almanac, but with additional details that are useful for planning observations.

An ephemeral guide

Almanacs are packed with astronomical data for observers and can be of use to the farmer or gardener in his or her annual work. By their nature, almanacs are ephemeral, recording celestial movements and the passage of time.

Scholar George Lyman Kittredge wrote: “Nothing is more strictly contemporary than an almanac… It is published for a time and becomes obsolete, by a natural and inevitable process, when its successor appears.” Almanacs provide information about the past, information for the present, and a glimpse of the future.

Leave feedback about this